| |

|

| |

| NOVEMBER 2015 ながら歩き texting while walking |

|

| |

|

| |

One of the greatest things about modern life is the 携帯電話 (けいたいでんわ; mobile phone). Along with that power, though, comes a great responsibility: to not use it while you are walking.

In an attempt to stop people doing ながら歩き (lit. “while walking”), train stations and networks have been pleading (politely) with their customers, having seen a recent spike in the number of accidents caused by people being so engrossed in their phones they’ve missed stairs/lifts/platforms. Posters proclaiming 「ながら歩きは危険です」(ながあるきはきけんです; Texting while walking is dangerous!) have become common on subways all around the country.

There are a few variations on the word you can use if you’re feeling fancy: ながらスマホ (lit. “while smartphoning”) and 歩きスマホ (あるきすまほ; walking while smartphoning) are both accepted terms.

|

| |

|

| |

| OCTOBER 2015 北斎 Hokusai |

|

| |

|

| |

There are few Japanese artists more famous than Katsushika Hokusai (葛飾 北斎), the man credited with popularising 浮世絵 (うきよえ; wood-block prints) in the rest of the world.

Little is known about his early life, but he rapidly became well-known in art circles, as he expanded from more traditional subjects (actors and courtesans) to more closely exploring both the daily-life of everyday people, and landscapes.

It is this second group of works for which Hokusai became most popular. His most famous collection, 富嶽三十六景 (ふがくさんじゅうろくけい; 36 Views of Mount Fuji), includes 神奈川沖浪裏 (かながわおきなみうら; The Great Wave off Kanagawa), which would become emblematic not only of Hokusai’s work, but of Japanese art in general. It has been reused and reappropriated many time since its publication in the early 1830s.

You can learn more about Hokusai at this year’s Japanese Film Festival, in the film Miss Hokusai. You can also learn more about woodblock prints at our current exhibition, Edo Giga: Comical Woodblock Prints from Japan.

|

| |

|

| |

| SEPTEMBER 2015 居眠り nodding off |

|

| |

|

| |

We’ve all been guilty of wanting to have a nap at work. It might have been a long weekend, or maybe a late-night sports match—or even just a Friday afternoon—but we all know the feeling.

Japan, too, knows this feeling, and has come up with a solution—the 居眠り (いねむり). Literally translated as “sleeping while present” (居る [いる]; to be present, and 眠り [ねむり] sleep), it particularly refers to the practice of Japanese office workers sleeping at work, either in their breaks, or during actual work hours.

居眠り is partially a response to conventional Japanese business systems, where many people stay late in the office for 残業 (ざんぎょう; overtime), and don’t get enough sleep at home. As such, when you walk into an office (or sometimes even a school classroom), you might find a few people slumped over their desks having a quick kip.

So next time you’re feeling sleepy at work, just tell your boss you’ll take 居眠り! We’re sure they’ll understand.

|

| |

|

| |

| AUGUST 2015 こぶし kobushi |

|

| |

|

| |

Contemporary enka (演歌) emerged after the war in Japan, and rapidly became a stonkingly popular form of pop music that echoed back to traditional Japanese music. The word enka itself was repurposed from an older form, but literally comes from 演じる (えんじる; to perform) and 歌 (うた/カ; song). A kid of Japanese blues, songs are often about past loves, or an idealised past Japan.

One of the defining features of enka is kobushi (小節), a kind of vibrato singers use on long, drawn out notes. This distinctive style of singing marks contemporary enka out from its predecessors, and is based on the unique scale used by the genre.

Don’t forget—if you want to learn more about enka, you can do so by signing up to our upcoming Language and Culture workshop here! Alternatively, check out our enka playlist on YouTube.

|

| |

|

| |

| JULY 2015 シャバーニ Shabani |

|

| |

|

| |

Meet Shabani (シャバーニ), a western lowland gorilla who has every woman (and some men) swooning. Originally born in the Netherlands, Shabani spent some time in Sydney’s own Taronga Zoo, before landing in 東山動植物園 (Higashiyama dōshokubutsu en; Higashiyama Zoo and Botanical Gardens) in 2007.

He seems to have lived a quiet life until this year, when social media exploded into a frenzy of love for Shabani. In the ensuing storm, a whole load of words have been used to describe him, including 魅力的な顔 (みりょくてきなかお; a charming face) and 引き締まった筋肉 (ひきしまったきんにく; toned muscles), but by far the word used most often is イケメン, a word that roughly translates to handsome man.

So do you think シャバーニ is an イケメン?

|

| |

|

| |

| JUNE 2015 自撮り棒 selfie stick |

|

| |

|

| |

If, like us, you’ve been to Japan lately, you’ll have noticed that a lot of people have taken to putting their mobile phones on the end of giant sticks to take photos of themselves in front of tourist attractions. That’s right—selfie sticks are big in Japan.

The word ‘selfie stick’ is fairly literal in Japanese: 自 (じ; self), 撮り (とり; to take [a photo]), and 棒 (ぼう; stick). If you want to say selfie in Japanese, you can just use 自分撮り (じぶんどり).

Though these things might have become unnecessarily popular in the last 18 months, an enterprising Japanese company actually invented the precursor to the selfie stick in 1983. The DISC-7 had a tiny mirror on the front of it so you could see yourself, while holding it with a stick.

|

| |

|

| |

| MAY 2015 涙活 tear seeking |

|

| |

|

| |

Have you ever felt like you just want to sit down and cry?

Fear not—Japan has the answer for you. Rather than trying to supress this feeling, a group in Tokyo is suggesting that the best thing for you is to sit in a room with other people and cry together.

涙活comes from 涙 (なみだ; tears) and 活 (いかす; to leverage). A few times a month, a dedicated group will get together and watch a sad movie, or listen to some sad music, or read out some sad poetry and cry together. They believe that this releases stresses in their body and detoxes the heart (心のデトックスを図る).

The idea has sparked interest all around the country—chapters have popped up in other cities, and you can even find a book of crying イケメン (attractive young men) in bookstores.

You can find out more at the official website.

|

| |

|

| |

| APRIL 2015 桜前線 cherry blossom front |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| By Manmaru (Own work) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons |

It’s spring time in Japan, which means that we are heading into the season of 桜 (さくら; cherry blossoms) and 花見 (はなみ; flower viewing)—the best time to be in Japan.

Japan is so taken with cherry blossoms there are whole industries dedicated to helping people find the best time to view them. The most important one is the 桜前線 (さくらぜんせん), or cherry blossom front, which started in the late 1960s as a way to track where the blossoms are opening, and how long it will be until full coverage is achieved.

If, like us, you’re about to head to Japan and want to know the best place and time to see the 桜 in bloom, there are whole websites dedicated to tracking the front—not just by prefecture, but by city. And, if you’re looking for some commentary on how this year’s front compares to past years, you can find that, too.

To see the 2015 front, you can read more here.

|

| |

|

| |

| MARCH 2015 落ち punchline |

|

| |

|

| |

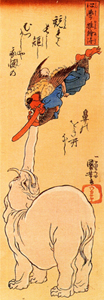

落語 (らくご) is a traditional Japanese humourous storytelling art. With only two props (a 手ぬぐい [てぬぐい; hand cloth] and a 扇子 [せんす; fan]), performers tell intricate stories, handed down from generation to generation of 落語家 (らくごか; rakugo performer).

Though Western stand-up comedians work to a rough structure in their shows, rakugoka are far more restricted in how they tell their stories. Each is expected to have a beginning (枕; まくら), a middle (本文; ほんもん), and then an end (落ち; おち; lit. a fall). This end, the 落ち, works much like a punchline in Western humour—a short, sharp line designed to turn the rest of the story on its head, and generate humour.

Don’t forget—if you want to learn more about rakugo, make sure to check out our upcoming series of events with Katsura Sunshine!

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

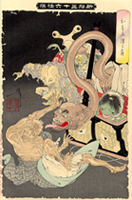

| JANUARY 2015 妖怪 phamtoms |

|

| |

|

| |

Japanese mythology is a strange and beautiful place. From 河童 (かっぱ) to ろくろ首 (ろくろくび), there’s a strange creature to satisfy everyone’s imagination. Japanese mythology is a strange and beautiful place. From 河童 (かっぱ) to ろくろ首 (ろくろくび), there’s a strange creature to satisfy everyone’s imagination.

Collectively, these creatures are known as 妖怪 (ようかい), and they have been part of folklore for more than a thousand years. Studio Ghibli fans might know that物の怪 (もののけ) is a synonym for 妖怪, highlighting just how central these creatures are.

While these stories and creatures have been around for hundreds of years Yōkai have been in the news over the past 12 months because of a small game called 妖怪ウォッチ, or Yokai Watch. This game for kids has its main character traversing the world with his Yokai Watch, which gives him the ability to see yōkai all over. She can then call on her yōkai friends to battle other, less kind, yōkai. (Younger readers may find these game mechanics worrying similar to another late 1990s Japan craze.) While these stories and creatures have been around for hundreds of years Yōkai have been in the news over the past 12 months because of a small game called 妖怪ウォッチ, or Yokai Watch. This game for kids has its main character traversing the world with his Yokai Watch, which gives him the ability to see yōkai all over. She can then call on her yōkai friends to battle other, less kind, yōkai. (Younger readers may find these game mechanics worrying similar to another late 1990s Japan craze.)

The Yokai Watch craze has spawned more games, toys, anime series, movies and YouTube clips. Make sure you keep an eye out next time you’re in Japan.

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |